A Conversation with Dr. Carrie Pettus

Ahead of her keynote lecture at the upcoming Utah Criminal Justice Conference, social worker Dr. Pettus reflects on her career dedicated to advancing justice through data-informed approaches

Dr. Carrie Pettus is a visionary social work scholar and innovator dedicated to advancing social equity and justice within criminal legal and justice systems. She is the founder and CEO of Wellbeing & Equity Innovations, a national translational research nonprofit that collaborates with justice and community partners to improve outcomes through research-practitioner partnerships. Dr. Pettus earned her PhD from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Social Work, and her MSW from the University of Kansas School of Social Welfare. She has served as a faculty member at Washington University in St. Louis and Florida State University, where she ran research labs and contributed to the advancement of social work education and research.

Across the country, jails and prisons have become default responses to untreated trauma, unaddressed mental health conditions and substance use disorder, and unmet social needs. But what if we invested in wellbeing instead of punishment?

Ahead of her keynote at the 2025 Utah Criminal Justice Conference, I spoke with Dr. Carrie Pettus, founder of Wellbeing & Equity Innovations and part of the Grand Challenges for Social Work Smart Decarceration Initiative, about her career as a social worker and the “5-Key Model for Reentry” her team developed and has implemented across eight states.

Read our conversation below, lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

Madison Hanna: Can you share what initially inspired you to pursue a career in social work and research addressing mental health, trauma, and mass incarceration in the U.S.?

Carrie Pettus: When I was in college, I was focused on getting a degree in psychology and I was working in various psychiatric hospitals and mental health settings. In that work, this whole notion of person-in-environment became really clear to me. Much of what's occurring with a person is influenced by what's going on in the context in which they're situated: where they’re living, their employment circumstances, and their relationships.

So, when I learned there was a profession that focused on that, I started to explore coursework in social work and I became hooked. I went on to get my bachelor's degrees in psychology and social work. Later, I earned my master's and PhD in social work.

In terms of work specific to our criminal justice system, that started when I was in high school. The pivotal moment for me was in a behavioral health sciences course when I was watching a video recording of Phillip Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Experiment. Essentially, it was a research study that took place in the basements of Stanford buildings, where half of the students who participated in the study were randomly assigned to be guards, and the other half were randomly assigned to be people incarcerated in prisons. The study analyzed the ways in which the two groups of individuals behaved toward each other. The results were dramatic, notably in the negative consequences at an individual level.

So, I started looking at this major societal intervention we have for behaviors that society, at any given moment, deems as inappropriate. When I looked at the greater social context, I learned that the way that we think about crime and punishment, justice, and public health is really flawed in this country. Fast forward a few decades, and I'm still doing the work.

"I think our country is incredibly fragile at the moment, and anywhere that we can support stability, wellbeing, and the potential for human contributions and human thriving, we should do that."

MH: What do you say to people like me—those who aren’t practicing in the fields of social work or criminal justice—who carry biases shaped by what they were taught about the criminal legal system, and whose privilege tells them there’s nothing wrong with the current punitive system?

CP: Our criminal justice and legal systems are very complex and disconnected. Even though a person has to get arrested to eventually go to court and go to prison (if they're convicted), the actions of law enforcement are not directly linked to the outcomes of incarceration. I think it’s important that people understand we have a very complex criminal legal and justice system in the United States. There are a lot of different decision points, and factors that influence those decision points.

Secondly, the laws for most of our crimes—that is, the laws about what is considered a crime—differ from state to state. For example, in some states the theft of an object that's over $500 is considered a felony, while in other states it is not a felony.

Third, as a result of failed public health systems, our criminal legal system has unintentionally become a default access point for resources. Although it was originally conceptualized that our criminal legal and justice systems were only used for criminal behaviors, that's not how it plays out in the United States. For example, people can get arrested for loitering or trespassing because they do not have a home and are living in a tent somewhere; not because they otherwise committed a crime. There are many, many, many different reasons as to why people become involved in our criminal justice and legal systems.

Finally, engagement in crime is not the biggest predictor of engagement in our criminal justice system in this country. The highly influential factors that contribute to whether a person gets convicted of a crime are the color of their skin, their socioeconomic status, where they live, and whether they have a substance use disorder or serious mental illnesses. This indicates that our criminal justice system has gone off course.

MH: Can you discuss your organization, Wellbeing & Equity Innovations, and your “5-Key Model” approach?

CP: Our organization, Wellbeing & Equity Innovations, is really focused on off-ramps or alternatives to criminal justice involvement, from first contact of law enforcement all the way to reentry from prison. We partner with criminal legal and justice practitioners to develop reforms that promote the wellbeing of individuals under supervision, professionals working in those contexts, and the communities that both are embedded in.

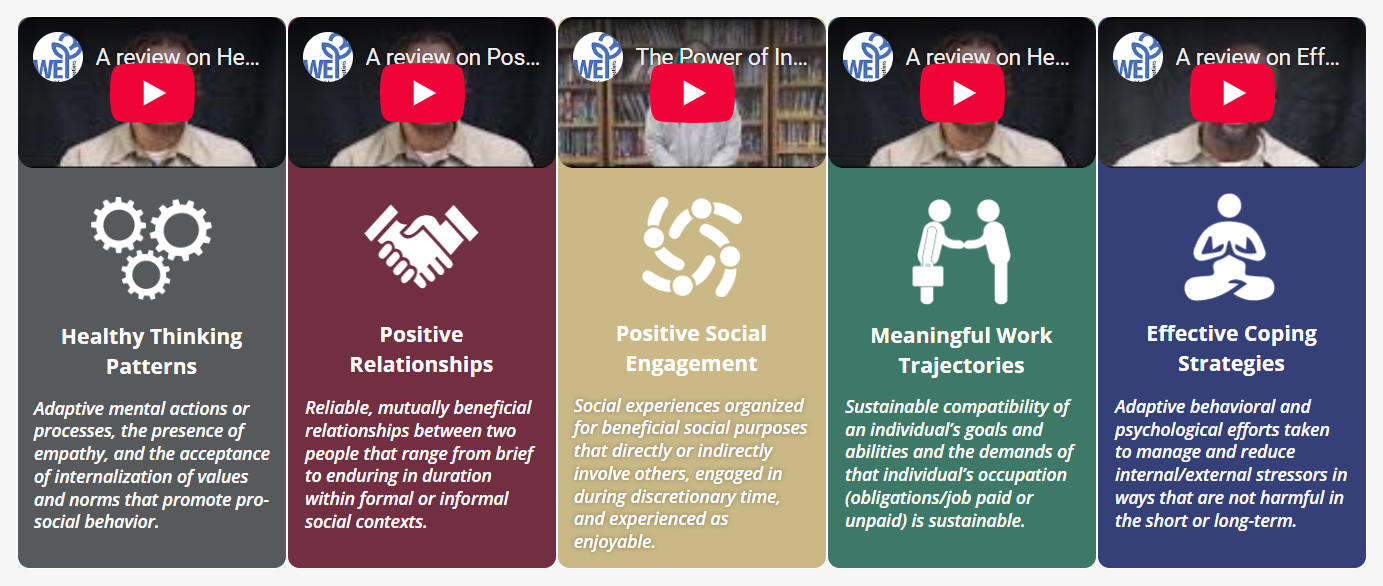

One of the approaches we developed is the 5-Key Model for wellbeing development. It’s based on a worldwide review of evidence of factors that best help people with overall wellbeing, especially those in highly marginalized or vulnerable contexts. Those five key factors are:

- Meaningful work trajectories

- Positive interpersonal relationships

- Positive social engagement

- Healthy thinking patterns

- Effective coping strategies

The model pairs evidence-based, individualized support with programming that helps individuals improve in those five areas and experience overall gains in psychological, social, and occupational wellbeing.

Over time, as individuals improve in each of the five areas post-incarceration, their wellbeing improves, and their likelihood of returning to crime and being reincarcerated decreases. We've tested it with thousands of individuals using randomized control trials and implemented it in eight states. Our outcomes are consistently good, which is exciting.

Click here to learn more about the 5-Key Model and other work. Screenshot, via Wellbeing & Equity Innovations website

"Our criminal justice system is set up like the consequences only impact the individual who's been accused of a crime, but that's not how it plays out in reality."

We also focus on family systems, trauma, and social equity work. Involvement in the criminal justice system is not an individual experience—it's a family one. Families are impacted by fines and fees, separation, and the ripple effects of disrupted employment and housing. Our criminal justice system is set up like the consequences only impact the individual who's been accused of a crime, but that's not how it plays out in reality. Our family systems work is twofold:

- We provide supports to families with a loved one involved in the criminal justice system.

- We work at the state organization and cabinet levels to help bridge agencies and improve coordination of resources.

Our trauma work acknowledges that 96% of incarcerated individuals have experienced at least one, usually three or more, significant trauma events. When untreated, trauma symptoms like aggression, impulsivity, engagement in substance misuse, and crime can all become factors that lead to justice system involvement. We work to treat those symptoms so that trauma is not driving people to engage in criminalized behavior.

Finally, we work with criminal legal and justice system partners to ensure fairness and justice, regardless of race, socioeconomic status, or behavioral health background. Many policies and procedures unintentionally exacerbate disparities, so we help to identify and solve for those areas to create more just experiences within the system.

MH: What resonated with me in your discussion about trauma and family systems is the impact incarceration has on the entire family unit and how these challenges are interconnected. As someone who is new to social work and criminal justice, I looked into criminal justice reforms and came across research on community-led response initiatives. I learned that by avoiding the removal of a person in crisis from their community, these strategies may improve outcomes post-treatment by preserving their connection to local support systems. In contrast, incarceration disrupts these support networks, perpetuating cycles of trauma—for example, when a parent is incarcerated, they are no longer present in their children’s lives. How effective are community-led initiatives in breaking these cycles and fostering healthier outcomes?

CP: Community-led response initiatives aim to help connect non-violent individuals experiencing a mental health or substance use crisis with treatment, as an alternative to incarceration. These crisis response teams have terrific data on keeping people out of the criminal justice system and in the mental health care they need.

There are numerous models for this and one of those models is called a co-response team. In that model, a mental health professional and a law enforcement officer work together to respond to a call from a community member about an individual in crisis. It's usually not a stranger walking by on the street or somebody in a grocery store seeing something; it's a family member calling from home about another family member because they are scared for their loved one's safety or their own safety, and they don't know who else to call. That's exactly the type of example where we don't need jail or prison for this person. It's just the only option that people know of because we don't have enough appropriate mental health resources in our communities to help keep people well and safe when they are not well.

We’ve talked to law enforcement officers and researched their perspectives, and most of them don’t want to be social workers or respond to mental health calls. They do because it's their job, but they don't feel equipped to do it. And they don't want to take people in crisis to jail, but usually that’s their only option to keep that person safe or the other people around them safe. Crisis response initiatives permit more appropriate responders to help with these calls and get an individual in crisis the care they need.

So, I think that's a great example that you've honed in on, not only thinking about it from a family systems perspective, but thinking about these other failed systems and mental health perspectives, too. It doesn't surprise me that that's really resonating with you and making sense, because it really does connect the dots around all of the factors that we've been discussing.

MH: Talking about the psychological effects of trauma reminds me of learning about Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) in my psychology program for my undergraduate minor. The research around ACEs underscores how profoundly these experiences of trauma serve as predictors for relationships and life outcomes. I think this strongly ties back to the concept of cycles of trauma and the importance of finding effective strategies to break those cycles within families. Reflecting on the importance of addressing these intervention challenges, I’m curious about your upcoming lecture. Can you share a sneak preview of what you’ll be discussing at the Utah Criminal Justice Conference?

CP: Close to two-thirds of people involved in the criminal justice system have either a history of some kind of mental health diagnosis or a history of substance use disorder. And, as I mentioned earlier, between 96% and 99% of individuals who are incarcerated in prison have a history of trauma.

What my collaborators and I have focused on is understanding the factors related to trauma that influence whether or not a person engages in crime. If we can address the problematic disruptions that symptoms from a traumatic experience can cause, we're more likely to not only support them in doing well while they're under criminal justice supervision, but we're also more likely to prevent them from ever coming into contact with law enforcement again.

| Click here to register and to learn more about the Utah Criminal Justice Conference, held in conjunction with the Generations Conference on May 19 and 20, 2025, 8:00 am to 5:00 pm at the Mountain America Exposition Center. |

During the keynote, I will discuss how nearly all individuals who end up incarcerated have serious trauma histories, and I’ll highlight the importance of treating trauma symptoms in all individuals, regardless of their incarceration history. I will address the challenges of treating trauma when people are living in volatile environments—such as prisons—and share strategies for providing effective treatment despite these circumstances.

While many conference attendees may not work in prison settings, they often serve individuals in similarly unstable situations, such as those who are unhoused or living in domestic violence shelters. These clinicians may benefit from learning about best practices in trauma treatment that have emerged from working with incarcerated populations.

Then, I will move on to discuss the role of the family in therapeutic interventions with people under criminal justice supervision. And, again, in this portion of the lecture, I will talk about what other helping professionals can take away from what we have been learning in corrections settings about intervening with the individual under supervision and the family as one unit. I am hopeful that the lessons and strategies we have learned can be applied to other community settings.

MH: What are some of the biggest challenges you have encountered in your work and how have you addressed them?

CP: That's a great question. I don't know if anybody's ever asked me that. I would say the three greatest challenges are complexity, distrust, and stigma.

Complexity would be two categories: complexity of the system and complexity of humans. It’s a very complex system and individuals are complex—both the people working in the system and those under supervision, which means that all of our intervention approaches need to be nuanced, responsive, and nimble.

There is distrust at every possible level of our legal and justice systems in this country, so for example, many communities don’t trust law enforcement. In turn, law enforcement officers don't trust many citizens, judges don't trust the attorneys or the clients, the clients don't trust the judges, and so on. We have this massive system with millions and millions of people going through it every year, and nobody trusts each other. It’s very hard to have a system and an individual’s experience function well when there’s no trust.

The third issue is stigma. As you mentioned before, not only is there stigma against an individual who has been convicted of a crime, but there’s a lot of stigma against the families that are connected to that individual. There’s even stigma against people who work in the system too, right? Stigma also surrounds individuals diagnosed with mental health or substance use disorders, particularly in communities where such diagnoses are seen as shameful or morally wrong. So, people who feel stigmatized or marginalized are going to be less likely to seek help. Then, oftentimes, the providers of mental health or substance use disorder treatment may stigmatize a potential client because they’ve been arrested or in prison before.

I've never had to simplify it like that before. I'm like, “no wonder this work so hard.”

MH: Yeah, there seem to be challenges at every level. With that, how do you stay motivated in the face of the challenges associated with this work? Why do you think this work is so crucial in today’s context?

CP: It's probably going to sound counterintuitive, but what makes me stay motivated are not the success stories, but the failures. We have a lot of people who have successful experiences and come out on the other side and I think that's fantastic, but more people are failed by the system. And the consequences are extreme suffering and tragedy, not only for them, but for their children and for the other family members they’re connected to.

"It's probably going to sound counterintuitive, but what makes me stay motivated are not the success stories, but the failures."

Secondly, the failed criminal justice system is really bad for our economy and our country in general. So, for me, it’s failures that keep me motivated. And that means I want to work myself out of a job! Because once there’s many more success stories than failures, I’ll move on to another system.

Why do I think it's important now more than ever? I think that beyond the criminal justice system, there are more expressions of anger, hate, distrust, stereotypes, and stigma today. I think our country is incredibly fragile at the moment, and anywhere that we can support stability, wellbeing, and the potential for human contributions and human thriving, we should do that. For lack of a better phrase, and I don't mean this in a negative way, but people involved in our justice system are a captive audience. I don't ever want people to have to become involved in the justice system, but if they do, we have an excellent opportunity to get them supports and their family members supports to prevent further harm at the hands of the system and prevent harm for the community.

MH: What has been the most rewarding aspect of your work in this field?

CP: The “light bulb” moment for people. To me, what's so rewarding is when, again, despite people's political background, social status, and all the different things, when they get it and see that this is not right: “I want to use my role and my status to do better and fix what’s broken about how we treat people so that everybody does well.” Believe it or not, there have been bipartisan efforts for about a decade or more to do better in terms of how we're treating human beings that get wrapped up in our justice and legal systems.

MH: Dr. Pettus, thank you so much for taking the time to talk with me today and for giving us a preview of what you’re going to talk about during your upcoming keynote on May 20th. We look forward to your lecture and we appreciate your valuable perspective on how criminal justice research can apply more broadly to wellbeing in our communities. Thank you.

Click here to register and to learn more about the Utah Criminal Justice Conference, held in conjunction with the Generations Conference on May 19 and 20, 2025, 8:00 am to 5:00 pm at the Mountain America Exposition Center.