Seeking Support & Stopping Stigma for Older Adults Experiencing Homelessness

One thing that Sarah Canham loves about gerontology is that it isn’t just one thing.

Gerontologists are trained in an interdisciplinary way to look first at the experiences

of older adults, and then to consider what’s happening around them. “Initially, I

didn’t have explicit training in housing or homelessness,” said Dr. Canham, associate

professor in the College of Social Work and the College of Architecture + Planning.

“What I did have training in was looking at the biopscyhosocial aspects of later

life.”

One thing that Sarah Canham loves about gerontology is that it isn’t just one thing.

Gerontologists are trained in an interdisciplinary way to look first at the experiences

of older adults, and then to consider what’s happening around them. “Initially, I

didn’t have explicit training in housing or homelessness,” said Dr. Canham, associate

professor in the College of Social Work and the College of Architecture + Planning.

“What I did have training in was looking at the biopscyhosocial aspects of later

life.”

So why did she start researching homelessness? Dr. Canham’s research is grounded in a community-engaged research modality, meaning she works with the community to identify their specific research needs and questions. She started researching housing because the community partners of the gerontology research center where she worked in Vancouver were seeing increased rates of homelessness and housing insecurity for older adults and they wanted to understand why. “One of the things that I love about community-engaged research is that what you’re doing is responsive to a need,” she said. “It’s not just research for the purpose of research; it’s research for the purpose of addressing a need from the community. In that way, our research is particularly impactful—not just for the purposes of furthering academic knowledge—but for the purposes of affecting policy or affecting practice or affecting service delivery to older adults.”

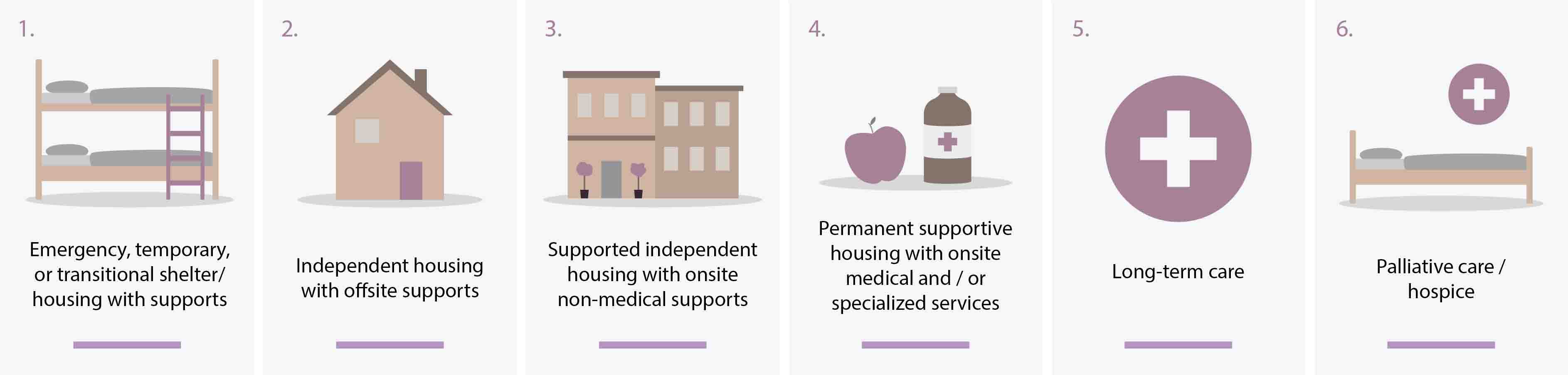

One of her main research projects right now involves evaluating promising practices for sheltering and housing older adults who have experienced homelessness. The project is extensive—it’s a five-year study that involves 14 investigators, nine adults with lived experiences of homelessness, and 40 community partners in three different cities. In the first stage of the project, now completed, the researchers did both an international scoping research review, and an environmental scan to determine the different types of shelter that existed for older persons with experiences of homelessness. This work yielded six categories.

Dr. Canham stressed the importance of thinking of these as housing-plus-support models, rather than simply solutions to housing. “When I think about homelessness, I don’t just think about those individuals, I think about the socio-ecological model that surrounds this population. It’s a view that has a micro lens, but then takes the mezzo and macro into account. It’s not just the older adults themselves that we need to be looking at; we need to be thinking about the health and social service systems that are available to support those individuals, and then the culture and the policies at broader levels and what impact those have on an individual’s access to services.”

Now, in stage two of the project, the group is using an evaluative framework to compare different models within the same category of shelter and care to each other. The goal is to figure out which practices are most effective in helping the population of older adults with experiences of homelessness. The researchers are asking What works?, For whom does it work?, and Why does it work? in an effort to determine best practices from the promising practice models they’re studying. “Older adults who have had these experiences of homelessness are a distinct population,” says Dr. Canham. “They have had different life experiences than your ‘average’ older adult; they have had different life experiences than the ‘general population’ of people experiencing homelessness. This is a unique population with distinct needs.”

For Dr. Canham, it’s important to keep an open mind with her research. “We have this nice categorization of models, but is this good enough? Is this actually what people want? Just because someone has experienced homelessness during their life, that doesn’t mean that one of these six options will work for them. What if they actually want something different? Do they have any choice in that? Our society tends to strip that away from people—that choice, that autonomy, that empowerment to be someone other than what people are labeling you as.”

“Homeism”

“We talk about racism and we talk about sexism and we talk about ageism—I grew up professionally talking about ageism in gerontology—but with my work and with housing, or people who are housing insecure, we do not talk about the stigma and discrimination they experience. We don’t even have a word for it. It’s not based on their age, gender, race or use of substances, but rather, the discrimination and stigma that people experience based on their housing status. I call it ‘homeism.’ We don’t recognize that the stigma and discrimination we perpetuate against those who are housing insecure is something distinct in and of itself. If we can actually accept the uncomfortable fact that discrimination around housing status is happening, that there is stigma associated with this topic, then perhaps we can change that. But we’re not even acknowledging it. If we’re not even looking at it, then how are we going to get to a place where that will change and look better?”