Kids of the Cocaine Epidemic: Coming to a More Complete and Complex Understanding

It began in the 1980s with the cocaine epidemic. The country was frightened. What was going to happen to a generation of kids whose mothers had used drugs during pregnancy? Were they going to be able to learn? Would they develop typically? Would they have brain damage? If there were adverse effects, was there hope they could become better? Similar to the questions that follow the opioid epidemic today, people were afraid that prenatal exposure to cocaine was having a serious detrimental impact on the future generation.

In effort to gain answers to some of these unsettling questions, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) funded multiple birth cohort studies across the country to investigate how a mother’s cocaine use during pregnancy would affect her child after birth. As the years went on, these studies continued to be funded, allowing researchers to continue to draw data and study long term developmental outcomes through multiple stages of the lifespan.

Enter Dr. Meeyoung Min, the new Belle S. Spafford Endowed Chair at the College of

Social Work. When she graduated with her PhD, she was looking for research that brought

together her interests in substance use, mental health, and maternity. She joined

a birth cohort study in Cleveland, Ohio, when the study children were about 6 years

old and has been researching the group ever since. Despite coming in to the study

late, given the longevity of the study, Dr. Min has been involved with the data collection

and analysis of this study for nearly 20 years. During that time, the questions she

and other researchers have asked of the data have become increasingly complex. What

began with a simple question—how does a pregnant mother’s cocaine use affect her baby?—has

grown over time into a multifaceted analysis of behavioral trends in a generation.

Enter Dr. Meeyoung Min, the new Belle S. Spafford Endowed Chair at the College of

Social Work. When she graduated with her PhD, she was looking for research that brought

together her interests in substance use, mental health, and maternity. She joined

a birth cohort study in Cleveland, Ohio, when the study children were about 6 years

old and has been researching the group ever since. Despite coming in to the study

late, given the longevity of the study, Dr. Min has been involved with the data collection

and analysis of this study for nearly 20 years. During that time, the questions she

and other researchers have asked of the data have become increasingly complex. What

began with a simple question—how does a pregnant mother’s cocaine use affect her baby?—has

grown over time into a multifaceted analysis of behavioral trends in a generation.

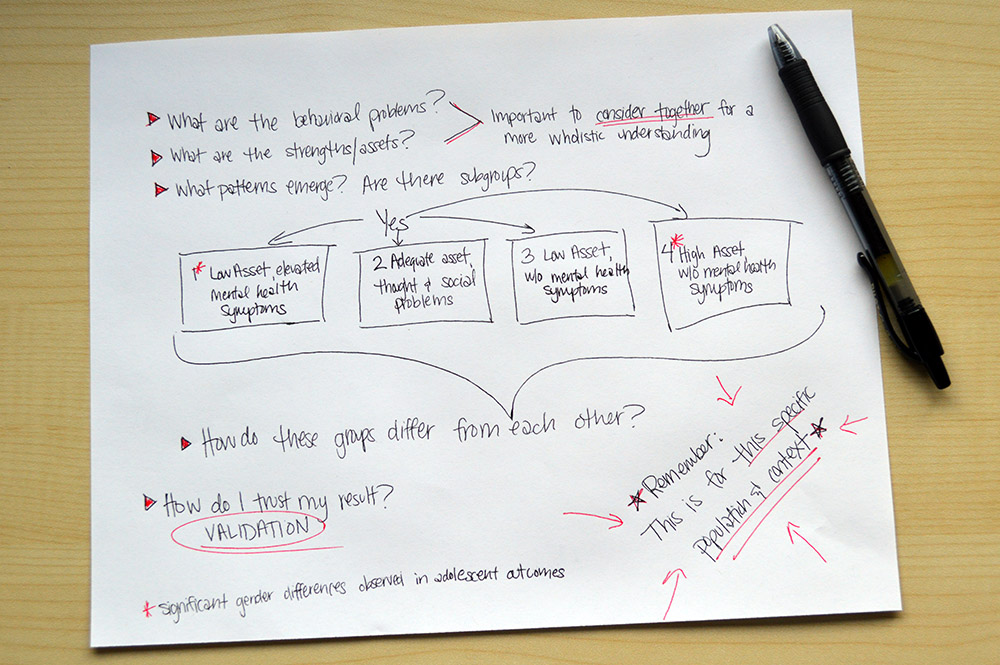

It's difficult to say where Dr. Min’s research is today without understanding the shifts her research has taken over time. Her first analyses involved looking at how maternal substance use during pregnancy was related to the developmental outcomes, such as intelligence and language development, of their children. As the children got older, she started looking at how those childhood trajectories were related to later adolescent engagement in risk behaviors—things like substance use, sexual risk behaviors, smoking—and gender differences within those groups. Her latest study added an analysis of the children’s internal assets (i.e., social competence, commitment learning, positive identity) and behavior problems and how those factors are moderated by their mother’s prenatal cocaine use.

One of the main themes that emerged from her latest study is the need for more support for girls with low assets and elevated behavioral problems (e.g., attention problems, thought problems, aggression). “Although the numbers are relatively few, these girls are having a lot more mental health problems, engaging early in sexual behaviors, and showing high risk in adolescence, which may lead to suboptimal young adulthood,” said Dr. Min. “As a researcher, I see this and wonder, why is this happening? What could explain this gender difference?”

It’s difficult to come up with one definitive answer, but she thinks part of it is the differing expectations placed on boys and girls. “I think culturally there is less room for girls,” she said. “Boys are allowed to explore many good and bad things and their inappropriate behaviors are more likely to be socially tolerated. But girls’ atypical behaviors are less accepted. Girls’ behavioral problems shown at an earlier age may indicate more severe problems than similar behavioral problems in boys.”

Dr. Min says it matters that the data for these groups was collected throughout their lifetimes. “Our past is colored by our current situation,” she explained. “If I’m doing well now, the past must not have been that bad. If I’m doing poorly now, it must have been a terrible childhood that put me here now.” She continued, “Prospective data collection adds validity to our findings.”

The next step, Dr. Min says, will include a look at additional life adversities—things like violence exposure, family conflict, sexual victimization—and how those events changed or impacted the child’s developmental trajectories. She also plans to study internalizing problems—things like depression and anxiety—in order to enhance understanding of child development in urban, high-risk settings characterized by poverty, discordant families, violent neighborhoods, and racial discrimination. “Moderation effects allow us to further refine the relationships between variables and provide a more complete picture.”

After almost 20 years of research focusing on the impact of mothers’ substance use, prenatally and postnatally, on child development, Dr. Min’s ultimate goal is to build a community—connecting research, practice, community, and policy—that supports substance-using mothers in becoming the mothers they wish to be. “I would like to provide parenting interventions for substance using mothers so their sense of enjoyment in taking care of their child can be restored. If we can bolster their parenting efficacy and enjoyment, their drug seeking behavior will be reduced, supporting their motivation to be a better mom.” She added, “If women know how to be better parents and can easily access the resources provided, they will do it. There is no person better for a child than their own mother. No one can underestimate that.”