A Lineup of Gaps in Eyewitness Identification

In 2013, Joanne Yaffe began what was supposed to be a “quick assessment of what we

knew was wrong with eyewitness identification” for the National Research Council of

the National Academies of Science. She didn’t know much about eyewitness identification,

but with her methodological expertise in meta-analysis and systematic review, it made

sense.

In 2013, Joanne Yaffe began what was supposed to be a “quick assessment of what we

knew was wrong with eyewitness identification” for the National Research Council of

the National Academies of Science. She didn’t know much about eyewitness identification,

but with her methodological expertise in meta-analysis and systematic review, it made

sense.

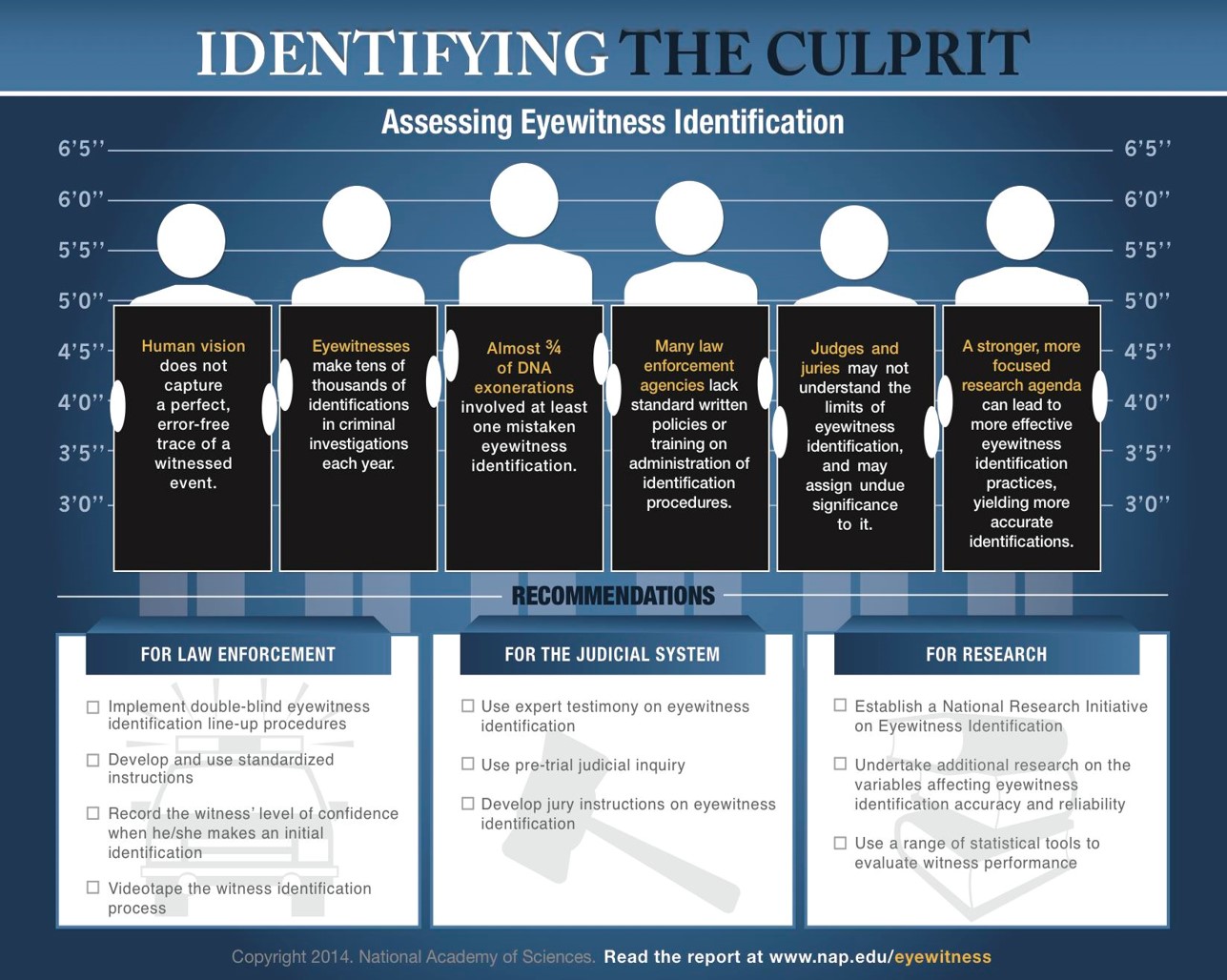

Five years later, much to her surprise, she’s still doing it. The research has moved past that initial report, Identifying the Culprit, to a several-year, interdisciplinary, multipart study on eyewitness research. The associated grant, selected by a panel of the National Academy of Sciences and funded by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, has ambitious goals. The research team is comprised of a law professor familiar with psychology and statistics, a psychologist with a background in memory research, a statistician with experience in forensics, and a social worker with a psychology background—Dr. Yaffe. The project includes research in jury decision making and the factors that influence a jury to weigh the uncertainties of eyewitness identification appropriately, the variables that affect a person’s ability to accurately identify perpetrators, statistical analysis across multiple variables, and a methodological review of existing research in the field.

Dr. Yaffe’s work is primarily in this last area—conducting an extensive systematic review of all the quantitative research ever completed in the field of eyewitness identification. This is a multistep process that includes several different types of analysis. First is an overview of available syntheses in eyewitness identification research. Using reproducible search strategies in multiple databases to identify these syntheses, these studies are appraised for risk of bias and categorized by the variables investigated. The findings and conclusions of these syntheses are recorded, and the primary studies included in the syntheses are identified and retrieved.

Next is a scoping review. Currently in progress, this part of the research includes new searches of research databases to identify all available primary quantitative studies of eyewitness identification research, some of which will have already been identified as part of the overview of existing syntheses. Information about the research methods used, findings, and conclusions of these studies will be entered into a relational database to make the findings available to both scientists and legal professionals.

This online searchable database will include all available research on eyewitness identification categorized across variables and type of study. Displayed in a visual, interactive, grid-like format, the database will very quickly show relationships amongst variables, where new research and syntheses are needed, and where high quality research has already been conducted. Because the grid will include both primary studies and syntheses, gaps in the research evidence base will be readily apparent.

Why go to this much trouble? Why is it necessary to review thousands and thousands of studies and combine them into a single database?

To Dr. Yaffe, the answer is simple: “There’s no one keeping track of where research is actually needed.” She continued, “This will be invaluable in helping to set the research agenda for the field. At a glance, researchers will be able to identify what research needs to be done.” Dr. Yaffe emphasized the importance of synthesizing primary research as systematic reviews. Researchers are under a lot of pressure to produce more research, and with no one keeping track, it is possible that the studies are being conducted where they are not needed, while areas of needed research are being ignored.

“I love systematic reviews,” she said. “They provide the most reproducible strategy for gathering all relevant research, appraising risk of bias, and compiling findings using quantitative and qualitative methods to synthesize available data. They show what’s needed in a way other research can’t.”

A Closer Look

Key recommendations from Identifying the Culprit included procedures to reduce eyewitness bias. Where possible:

- Investigating officers should not give feedback to the witness if they’re correct or not (could be as simple as an eyebrow raise).

- Investigating officers should tell the witness the person might not be in the lineup so they don’t feel pressured to choose someone.

- Investigating officers shouldn’t know or suspect who the perpetrator is, by “blinding the investigator” so that they cannot see which suspect has been identified by the witness.

- If this isn’t possible, investigating officers should not be in view of the witness as they look at potential perpetrators.

These and other recommendations were adopted almost immediately after publication by several influential jurisdictions. “Legal professionals—police investigators, prosecutors, and judges—want to be able to identify the correct culprit and to avoid ‘false positives,’” said Dr. Yaffe. “They are hungry for solid research in this area.”

She also stressed the need for more studies. “No single study is perfect in and of itself. The statistical standard of accepting that something is real if it can happen less than 5% of the time by chance alone means that approximately 1 in 20 studies are flukes. Some replication of research is necessary, and it is important that studies be reported in a reproducible way. We need syntheses of multiple studies to know what relationships are real and which are not. Once high quality syntheses have established robust relationships among variables, additional primary research may not be required and may actually represent a waste of expensive research efforts.”

When asked to reflect on her years in eyewitness identification research, when asked why she continues to do it, Dr. Yaffe said, “I’ve learned how important this is. People are being erroneously convicted. We need to do better.”