A Grandmother Epistemology

If innovation is thought of as a process of looking forward to the future, with excitement for new and fresh ideas, then this story is the opposite of that. This is a story about looking to the past and reintegrating wisdom that we once held and lost, or worse, never took the time to understand before dismissing it. What is exciting and new about this story is the ways these social workers are reclaiming their heritage and infusing their identity into their practice.

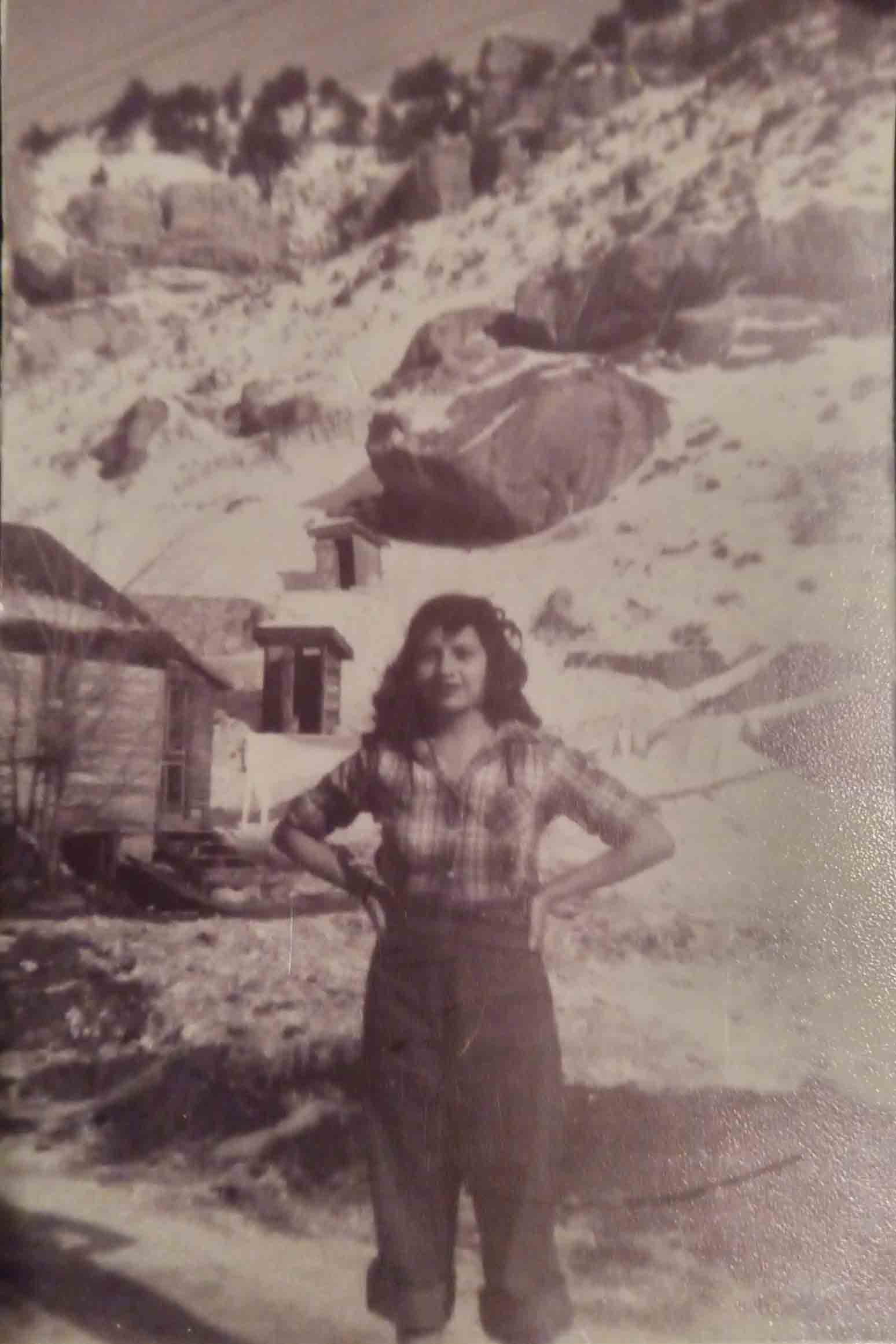

Yvette Romero Coronado's grandmothers,

Maria del Carmen Armijo & Guadalupe Romero

But before we get into the details, let’s lay some groundwork.

One thing Sonya Martinez-Ortiz and Yvette Romero Coronado have in common is that they lost their grandmothers as young adults; a fact that brought them together when they began working together at the University of Utah College of Social Work as clinical professors in the field education office. Their grandmothers were key nurturers and teachers in their lives, even when they didn’t fully realize it. “My grandma was the first social worker I ever experienced,” said Romero Coronado. “She would take me on visits to family, friends, and neighbors' homes, listen to their problems, and do what she could to help them. She was my original social worker.”

Romero Coronado’s grandma was a practitioner of the ancient rituals and medicinal practices that can be found in curanderismo and other Meso-American healing practices grounded in the culture, plants, food, traditions, and spirituality of indigeneity and Catholicism. Both Romero Coronado and Martinez-Ortiz saw this kind of medicine at work in their childhood communities, and both were discouraged—primarily through cultural silence and colonial shame—from understanding their grandmothers’ practices more deeply.

But as they were both beginning their jobs at the College, they felt a call to reconnect to those cultural traditions, to return to that ancestral wisdom. Rather than grounding their work and their lives solely in the cognitive practice they’d spent years studying, they felt a call to move their work to a different space. “When I think about my experiences becoming a therapist, I felt like I had to learn things perfectly and understand theory perfectly,” said Martinez-Ortiz. “But that mentality gets in the way of centering the people and communities I’m working with and a part of. I had to incorporate my understanding of practice and theory into my body’s intuitive ways of knowing. This intuition isn’t something that’s celebrated in the Western view, but it’s essential to the heart of social work.”

Romero Coronado agreed. “When we let go of the cognitive and started listening to our inner wisdom, we entered into a space that has always been there.”

Sonya Martinez-Ortiz's grandmother,

Edulia Gomez

It can be difficult to provide a picture of what that looks like in practice—there isn’t one universal way of ancestral wisdom. Sometimes it’s limpias/cleansings. Other times it’s sensory stimulation—using particular herbs and oils or drum beats for somatic release or enjoying good food. Indigenous knowledges can take many forms. And what that space of wisdom looks like for Martinez-Ortiz and Romero Coronado has shifted over time as they’ve learned more. Their understanding of curanderismo or traditional medicine has grown as they have practiced the teachings of their grandmothers and other generous teachers in the community

That being said, there are certain things that remain constant. As mentioned above, indigenous medicine is centered in the body. Romero Coronado explained “There is wisdom in the body. Accessing this wisdom begins with recognizing that your body is giving you information that can help you heal.”

And not just your body. Another expansion of Western healing methods that has long been at the core of indigenous medicine is an awareness of the whole person. A person isn’t just a body. They are also a mind and a soul. They are connected to their environment, the water, plants and beings within it. True healing comes from looking at all aspects of a person, expanding awareness of what needs healing. “Healing never happens in a silo,” said Martinez-Ortiz. “If you want to create space for healing, you need to tap in to the mind-body-spirit connection.”

Indigenous healing is also deeply rooted in community. While Western treatment often focuses on isolating individual factors when addressing mental and physical health needs, indigenous medicine looks at and seeks support from the systems a person is housed within as the starting place for healing. “Healing isn’t an individualized practice; healing lives in the collective,” explained Martinez-Ortiz. “This work aligns with womanist thought. The responsibility we hold for each other requires us to be more expansive. We are bound together—you can’t disconnect me from we.”

Yvette Romero Coronado

We often means those biologically closest, but Romero Coronado and Martinez-Ortiz know that isn’t always the case. Although their journeys have been deeply guided by their grandmothers, they know this isn’t the way for everyone. Some people aren’t connected to their ancestors. Some people don’t have access to their communities due to war or conflict or adoption. No matter a person’s circumstances, Romero Coronado and Martinez-Ortiz believe there is space for people to situate themselves within this work. “We don’t all know our ancestors, but we all carry some of their wisdom,” said Romero Coronado. “It might be a meal or a song, a curiosity to know more, or deep intuitive feeling. Listening to the sparks inside you may give you guidance or answers to your questions.”

As more people engage with indigenous wisdom, Martinez-Ortiz and Romero Coronado are both excited and concerned. They’re thrilled to see an expansion in knowledge. “This kind of culturally responsive practice has major cultural, spiritual, political, and linguistic impact,” said Martinez-Ortiz.

Romero Coronado agreed, “When students and clients see and hear and feel themselves in practice, it’s healing. I want to live in a world where people feel affirmed and have the ancestral tools they need to heal.”

Sonya Martinez-Ortiz

They also have reservations about the ways this wisdom might suffer if accessed in the wrong way. They fear that if studied in appropriative ways, indigenous medicine will suffer from continued commodification. A number of widely practiced therapeutic methods taught and utilized today have deep roots in indigenous knowledge that reach far back, long before Western researchers began exploring them. Martinez-Ortiz explained, “Our bodies and our communities have always had wisdom, it just hasn’t always been listened to.”

Romero Coronado and Martinez-Ortiz know that ancestral medicine won’t appeal to everyone, but for those who feel called to this path, they should engage the practice thoughtfully and without co-optation. “This work isn’t always comfortable,” said Martinez-Ortiz. “In fact, it’s not meant to be.” Both Martinez-Ortiz and Romero Coronado emphasized that this medicine can’t heal unless we take a collective moment to address historical and ongoing colonization. Colonizer. Colonized. A mix of both. We live in a world that was literally built by taking from some and giving to others. Accessing this medicine means sitting with that. “There’s a reality in the fact that colonization has hit everyone,” said Martinez-Ortiz. “Our systems, our communities, even ourselves are rooted in internalized colonization and rejection of indigeneity. The personal is political. The political is personal. The question we ask in this work is, how do we invite people in to that, in respectful ways?”

“You have to engage with the complexity,” said Romero Coronado. “You have to be willing to be uncomfortable, to grapple with it.”

We acknowledge that there are still communities that don’t get proper recognition and support for the work they do to keep indigenous practice strong. We invite others to consider the complexity of colonization and the co-optation of traditional knowledge that has occurred without giving credit to the original indigenous practitioners.

Yvette Romero Coronado continues to serve as a faculty member in the College of Social Work. Now executive director of a community agency, Sonya Martinez-Ortiz remains connected to social work education through her service on the College of Social Work’s Community Advisory Board and as a field education supervisor.