Waves of Change:

Creating Culturally Responsive Therapy

PhD candidate Lani Taholo has been in the community for as long as she can remember. It started with pies her mother made for her neighbors when she was in middle school. Often she would come home from school and there would be pies waiting to be delivered around the neighborhood. “It was part of my homework when I came home,” she said. Throughout high school and into college Lani continued to find ways to stay actively engaged with community building efforts, feeling a call to continue. She didn’t know what it was, but she knew it was what she wanted to do. She remembers asking a mentor, “What is this? Helping people? Being in community? What is this? I want to do this. Is this social work?” Her mentor told her it was, and her direction was set.

Lani has had extensive social work experience in the decades since then. After earning her BSW and MSW, she worked for 20 years in DCFS, wrote curriculum for the state office for criminal and juvenile justice, reworked legislation for family group conferencing with indigenous families, and continues to run a highly successful culturally responsive private practice. Through it all, the need for cultural integration into mental health practice has resurfaced again and again.

Seeing the need and feeling compelled to address it, Lani decided to pursue a PhD with the aim of creating the culturally relevant mental health curriculum that was lacking in the field of mental health and trauma. Current research suggests that mental health services are highly underutilized by Pacific Islanders, many barely making it past an initial therapeutic assessment despite high need, and she wanted to understand why.

In order to achieve this, her dissertation project included two phases. First, she conducted multiple focus groups, including as many people as she could—Pacific Islanders from age 29 to 72, from Logan to Utah County locally, with a few participants calling in from the islands; coaches, parents, teachers. She wanted to hear as many community voices as possible to capture as much as she could about the specific mental health needs Pacific Islanders are facing.

The data that emerged is extensive. And powerful. Combing through almost twenty hours of data, Lani found a wellspring of information re-emphasizing the need for a different approach to mental health for her people. “Therapists today are using a Western cultural assessment tool for a non-Western way of living,” she explained. One example is how family relationships are usually addressed in therapy. Most intake assessments that are currently used ask a variety of questions around why the person has come in to the office that day. Questions like, “What is the reason for your visit today? What do you hope to accomplish? What are your long term goals for therapy?” These questions all center around “you.” But for Pacific Islanders, this approach doesn’t make sense.

Lani explained, “Family is essential to Pacific Islanders. Our value comes from the role we play within our family and how it contributes to the family. Everything is family centered. If the therapist doesn’t know this, doesn’t look for this in the initial assessment, and doesn’t ask about family in a way that’s integrated with who we are, why would a client come back?”

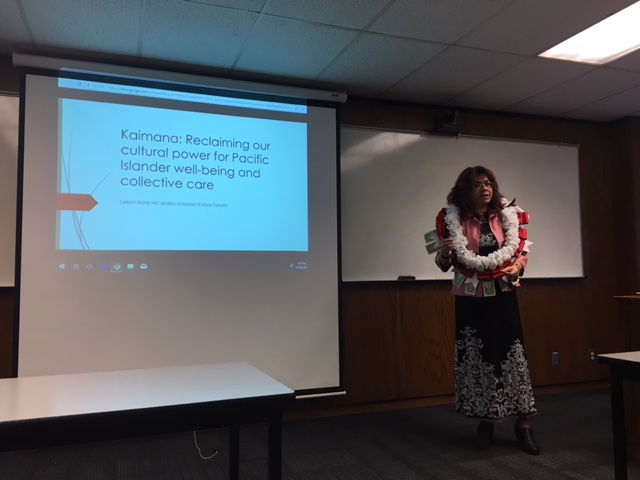

This is only one of the insights Lani gained from her focus groups. Participants talked extensively about a multitude of factors contributing to the non-relatability of mental health services. These include, but are not limited to, the loss of indigenous language, the changing role of elders in the community, and a different understanding of the purpose of life, and a loss of connection to nature. With this information in hand, Lani created an indigenous mental health curriculum focused on addressing mental health issues around violence, suicide, and self-harm—some of the major mental health issues that emerged from her focus groups. The program, Kaimana, centers Pacific Islander cultural values as the primary way to address these issues.

“Kaimana” is an Islander word that means divine power from the wave of the sea. Lani explained, “Instead of the waves of life becoming overwhelming—waves of depression, waves of anxiety, waves of trauma—through divine power and the resources of our own people, our own indigenous practices, we can become one with the wave, as our ancestors did with the waves of the ocean.”

So far, Lani has run two full Kaimana programs. Though the programs were slightly different based on the needs of the group, both included nine sessions and were grounded in Pacific Islander cultural concepts as a way of addressing critical mental health issues. “Participants coming out of the program have been on fire,” said Lani. “These participants are now movers and shakers in the community—doing whatever they can to address mental health concerns in our Pacific Islander communities. According to the data, Kaimana spoke to their core and who they really are in a way other approaches haven’t.”

For her work in developing this curriculum to address the underutilization of mental health services among Pacific Islanders, Lani was presented with the Salt Lake County Hero Award—an award presented by the Salt Lake County mayor to recognize innovative work with Salt Lake County’s diverse communities. Family and friends joined her on stage as she accepted the award from then Salt Lake County Mayor Ben McAdams.

As Lani prepares to cross another stage—this time for earning her PhD from the University of Utah—she is also preparing her Kaimana curriculum for publication so it can be used in other indigenous communities. “The purpose of Kaimana is to pipeline indigenous mental health approaches all over so people don’t have to wait,” she said. “We need this now.”